In February 2019, I spent a three week art residency at Textílmiðstöð Íslands, the Icelandic Textile Centre in Blönduós on the Northern peninsula overlooking the Greenland Sea.

The purpose of my art residency at the Textile Centre was multi-faceted.

At home in the Outer Hebrides in Scotland, I am both an artist but also a shepherdess of a flock of Hebridean sheep with a knitting yarn business The Birlinn Yarn Company.

It is believed that the ancestors of my sheep were brought to the Hebrides by Norwegian Vikings around 850AD. Hebridean sheep are part of the North Atlantic Sheep breed and are related to Icelandic sheep that were also introduced to Iceland by the same Norwegian Vikings.

I was, therefore, interested to find out more about the ancestry of my Hebridean sheep, to research the Viking link between the Hebrides and Iceland and to spend time with Icelandic sheep farmers.

Of course, paramount to this was the opportunity to set aside time for new creative practice but this time bringing together my life as a crofter/shepherdess and art work.

What surprised me during my residency was discovering the strength of the link between Iceland and the Hebrides. Icelanders refer to the Hebrides as ‘suður eyja’ the Southern Isles. In the Icelandic Book of Settlement ‘Landnámabók’, Shetland is referenced twice, the Faroes three times, Orkney seven times but the Hebrides are mentioned twenty-two times. Many of the early settlement areas share place names with the Hebrides such as Hekla, Grimsay, Pabbay and Barra. There are in fact several places in Iceland named after our island of Berneray, which I discovered is named after the blond headed warrior ‘Bjorn’.

Further to this, through genetic studies it has now been concluded that 80% of the settling males in Iceland were from Norway whereas 62% of the settling females were Celtic or Hebridean. However, to further strengthen the case for links with the Hebrides, it has been discovered that there are two kinds of mitochondrial DNA that are unique to only Icelanders and Hebrideans. So it seems that the link between Iceland and the Hebrides is much more than just sheep.

‘The Laxdaele Saga: the story of Aud the Deep Minded’ and her family, is a romping Norse tale of war waging, love and bravery.

Aud the Deep Minded is recognised as being the first and possibly only woman to establish a settlement in Iceland in her own right in 895 AD.

She was born to Ketill Flatnose a mighty and high born ‘hersir’ chieftain in Norway. However, the rise of the domineering King Harald of Norway meant powerful families had to either give up their lands to the King, be chopped into pieces or flee. Ketill Flatnose chose the later and fled to Ireland where Aud married Olaf the White, the self-appointed Norse King of Dublin. Olaf was a hot headed warrior who, after the birth of their son, was killed in battle.

Aud then fled to the Hebrides where, in due course, her son Thorstein married and had a family of seven children. They were settled there for some time until Thorstein, who had taken to warring far and wide in Scotland, was killed by his own men.

Aud was at this time in Caithness, she then commissioned a ‘knarr’ a Viking ocean going boat to be built in secret in the woods. On its completion, she gathered all her remaining kinsfolk and men of high status as well as several slaves and set sail, with herself as captain, first to Orkney, then Faroes (marrying off her grand daughters en-route) and finally arrived in Iceland to claim settlement lands in the Broadfirth-Dales in 895 AD. In due course, she divided up her land amongst her people and announced her slaves free men of Iceland.

For so many reasons this is a great saga of Norse history, the migration of their people and a powerful, intelligent female leader. It also further demonstrates the strong links between Iceland, Scotland, Hebrides and Ireland.

During my art residency at the Icelandic Textile Centre in Blönduós, I focused on exploring the qualities that are specific to North Atlantic sheep fleece. These fleeces have two layers: an outer layer ‘tog’ with fibres 8-12cm long and an inner layer ‘thel’ which is short and fluffy.

This is a characteristic shared with both Icelandic and Hebridean fleeces so it was very relevant research.

The resulting art works explored the different qualities of these fibres through knitting, felting and binding. They also responded to the cultural heritage of wool work dating back to the Vikings and more recent times.

Roagvalfeldur cowl

The Vikings wove the long outer layer ‘tog’ wool fibres into what was called ‘roagvalfeldur’. This was then worn as a furry cloak that, due to the water shedding properties of the ‘tog’ fibres, was both weather resistant and warm. This fabric was so valuable that it was used as a trading pile from 850 AD until around 1350 AD in exchange for other goods.

Instead of weaving, I experimented with knitting these long fibres into a cowl. The result was quite successful and I plan to knit the long fibres of our Hebridean sheep into a similar cowl though in black Hebridean fleece to contrast the white Icelandic fleece.

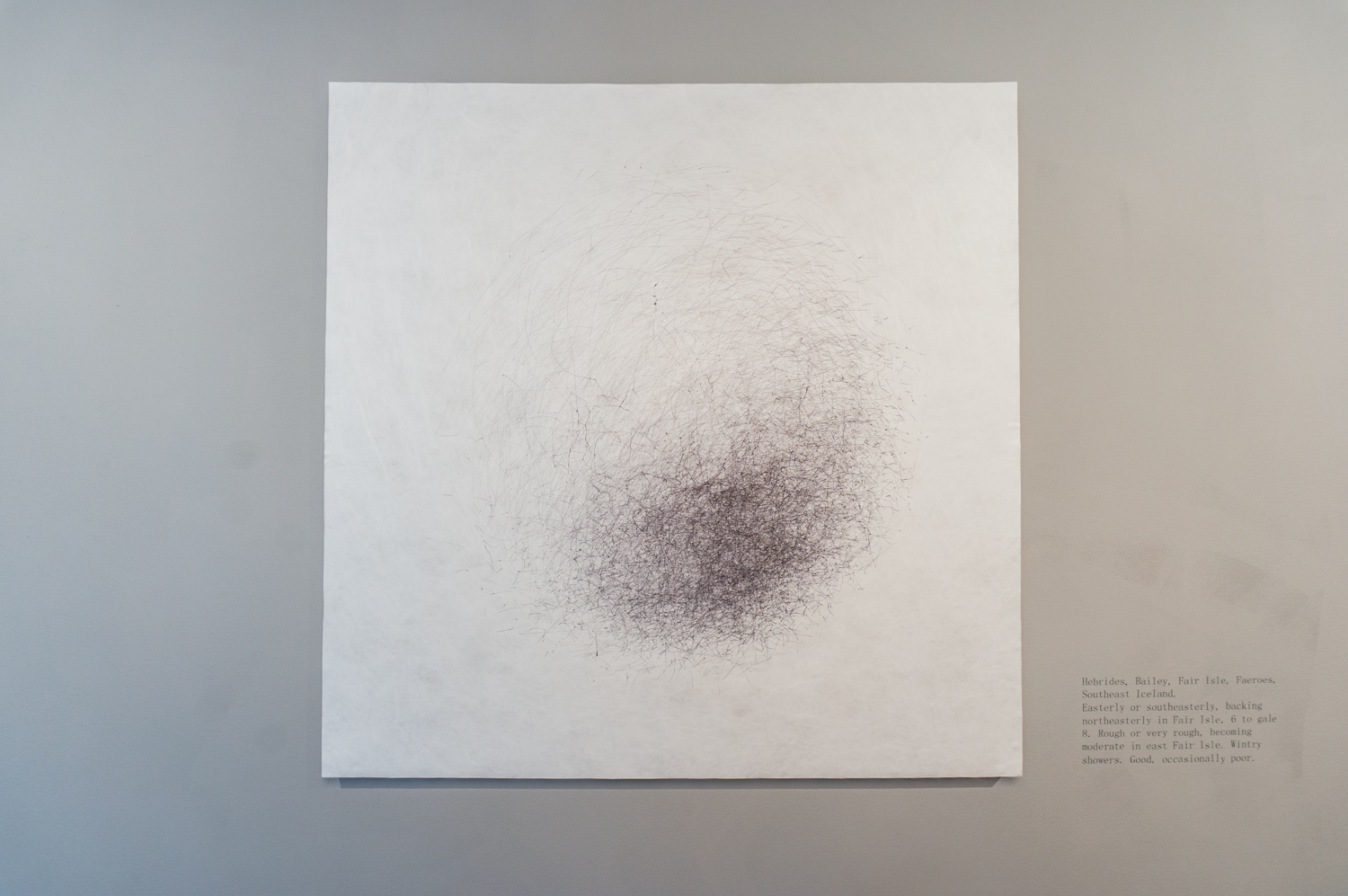

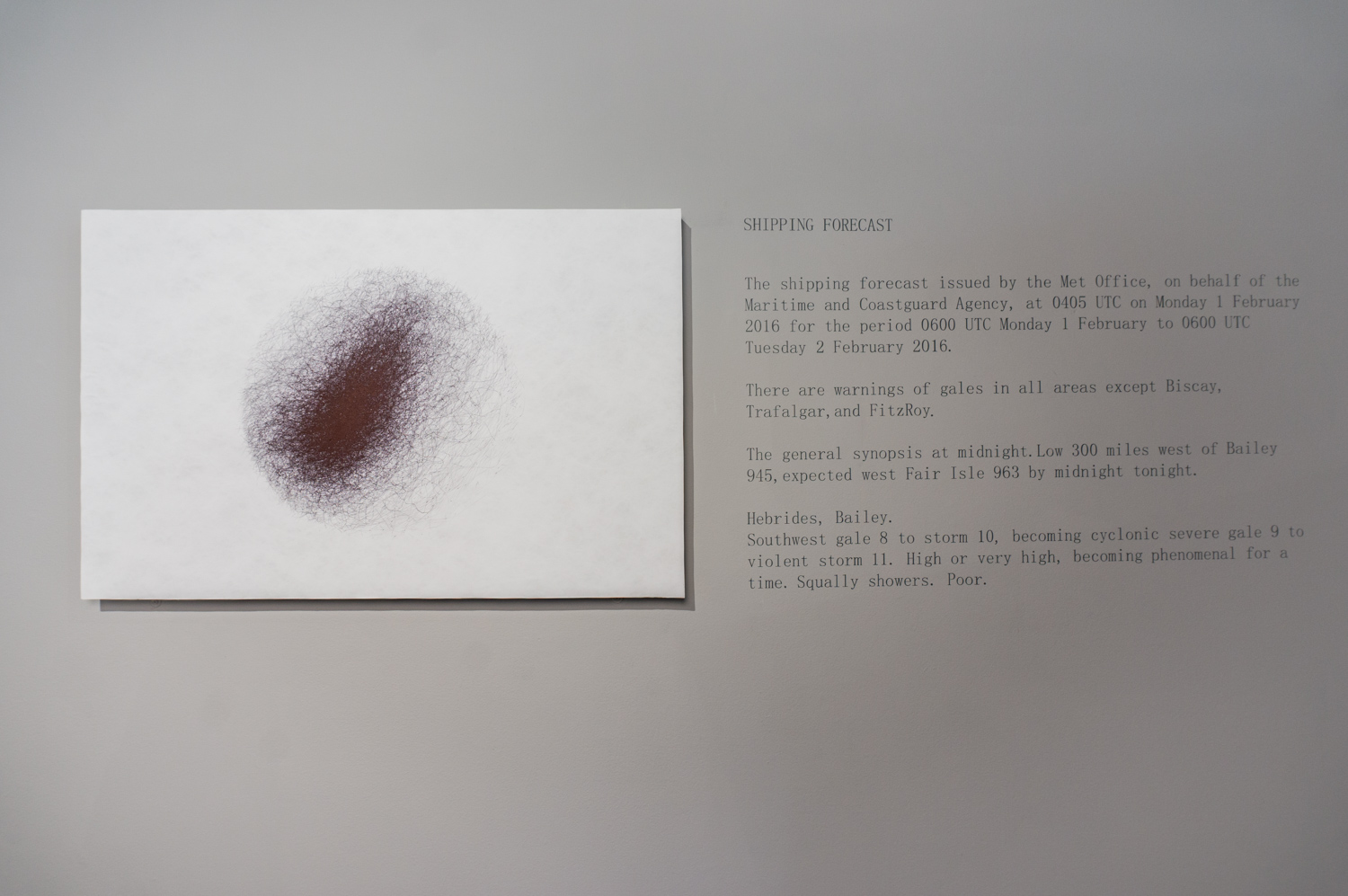

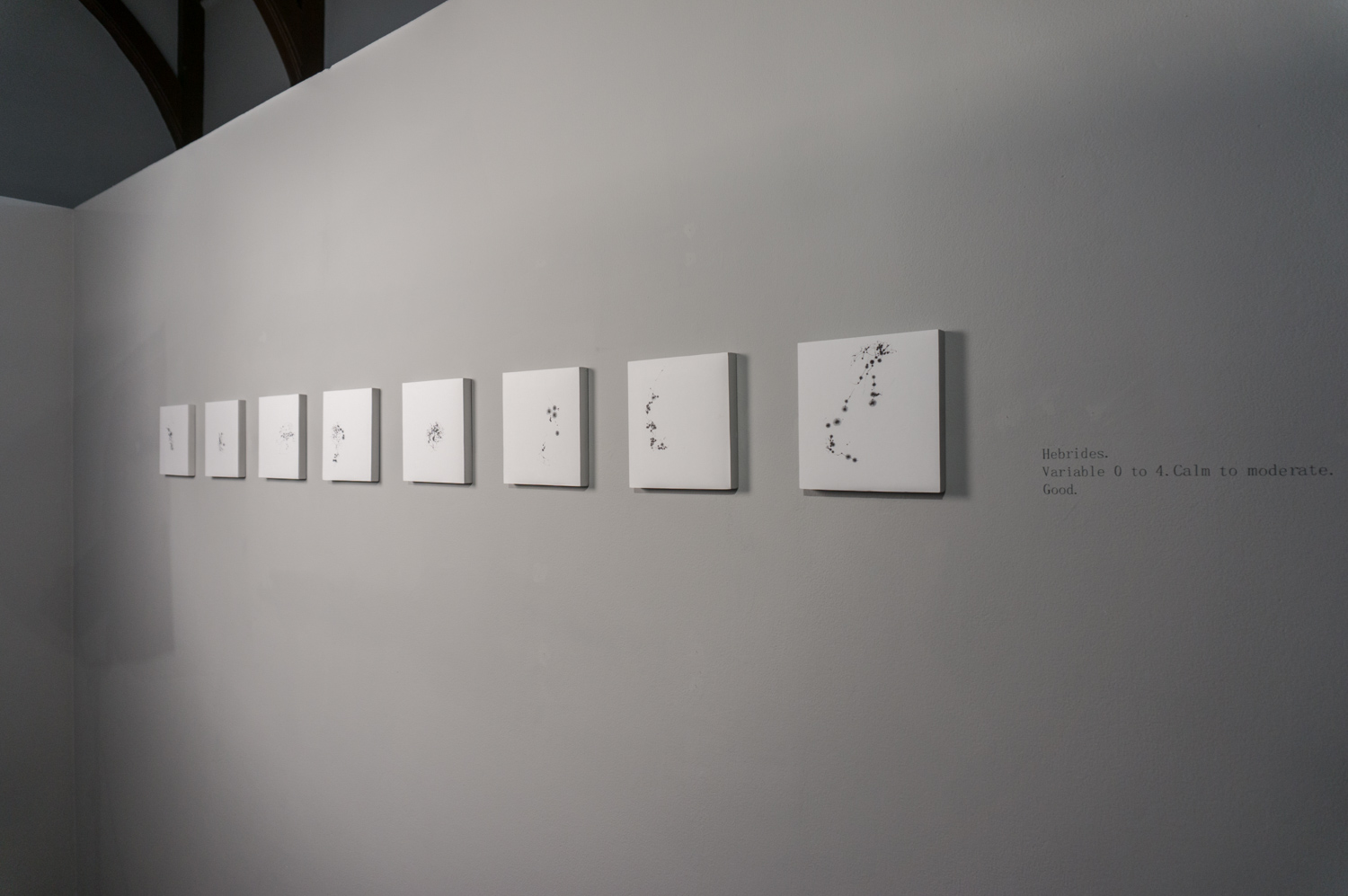

Felting DNA

Part of the aim of this visit to Iceland was to discover the history and potential genetic links between Hebridean and Icelandic sheep. My work represented this genetic variation through exploring the different colours of North Atlantic sheep, which range from black through various greys and light browns to pure white. I did so by felting the under fleece fibres ‘thel’ into hollow sausages which were then snipped into ‘polo-mint’ shapes. By laying them out flat a picture begins to build of the huge range in fleece fibre colour. This is still a work in progress as my aspiration is to collect as many fleece colours as possible from all the North Atlantic sheep.

Pradaleggur Sheep Skulls

On my visits to the sheep farms I was often presented with a ‘pradaleggur’, referred to as being made by the farmer’s mother or grandmother. A ‘pradaleggur’ is a sheep thigh bone scrapped clean and sometimes coloured, around which was meticulously wrapped tapestry threads as a means of keeping them. The resulting thread patterns were very beautiful and the women took great pride in the process of carefully wrapping them. Icelanders have been historically resourceful with nothing going to waste, hence why they use the bones as a useful object. In our culture, we have become quite bone adverse and I was interested in the beautiful patterning of the tapestry threads contrasting the material quality of bone.

I was kindly lent several sheep skulls by local farmers for my research. I explored the potential of the ‘pradaleggur’ by wrapping weaving yarn around the horns and skull bones. By combining different coloured threads this produced interesting patterns which for me were reminiscent of Harris tweed. At the end of my residency, I returned the skulls but some farmers were very happy to receive them back with their horns wrapped with threads.

I would like to thank all the staff at the Icelandic Textile Centre for making us so very welcome and for all their help and advice during our stay. The art residency was everything I could have hoped it would be and I would thoroughly recommend it if you get the opportunity.

I am also very grateful to Comhairle nan Eilean Siar and Creative Scotland for the Visual Arts and Craft Makers Award that I received which made this wonderful experience possible.